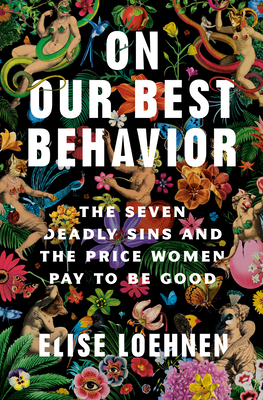

Title: On Our Best Behavior: The Seven Deadly Sins and the Rise Women Pay to be Good

Author: Elise Loehnen

Find on The Storygraph or Goodreads

Buy Here: Bookshop.org | The Novel Neighbor | Barnes and Noble

Publishing: May 23, 2023 by The Dial Press {Penguin Random House}

Format: Hardcover

Source: Unabridged Bookstore {Chicago}

Genre: nonfiction

I picked up this book this summer after–well I can’t remember where I first came across it. I remember not being able to request an e-arc from Edelweiss but can’t remember if I found it looking through catelogues there. Regardless, I had this on my radar but had put off purchasing it until I was in Chicago in July. I was on a mini bookstore crawl with one of my bestest friends Hopie (hi!!) and knew I had to bring it home with me.

The premise of this book is that journalist Loehnen walks through each of the seven deadly sins and interrogates the reasons why “women” (although Loehnen’s “woman” really means white-cisgender-able-bodied-straight-etc) are effected into the 21st century–even if said “women” do not prescribe to the religious (Christian) ideals that so heavily promote(d) the seven deadly sins in the first place. The book opens with two brief sections on “Genesis” and “The History of the Patriarchy” which are possibly the most well researched and grounded portions of the text. Loehnen outlines the history of the seven deadly sins and explains how they were codified into Christian law despite never appearing in any text within the Christian Bible–a fact that continues to astound me. These portions of the book skim the waters of Christian theological history, but the strongest point Loehnen manages to get across to her readers is the fact that though the Bible (particularly the New Testament) may be considered by Christians to be the “word of God,” human beings decided which Gospels were included and which (like Mary Magdalene’s, for example) were considered heretical (and thus excluded from compiled versions of the New Testament). My biggest gripe with this portion of the book was the “permission” Loehnen gives to her reader to skip these chapters–perhaps its the historian in me, but I can’t help with disagree with her. These chapters give essential context to understanding the long lasting cultural conditions to which Loehnen refers.

The next chapters walk through each one of the seven deadly sins. Loehnen combines self-reflection (memoir style) with broad generalizations about how each of the seven deadly sins–and particularly a woman’s pursuit to overcome them–percolates into the modern era. Each chapter ends instead with a mantra style statement that argues instead how each of the sins resembles some basic human (female?) instinct/tendency and actually can be ~good.~ At its most basic, this book is all over the place. Loehnen is a journalist and this was not the well researched social science/historical text I thought I would be reading. At one point Loehnen cites a “study” from 2008–in a book published fifteen years later–without any interrogation as to why said study hasn’t been replicated in almost two decades. This book meanders and it generalizes to a baffling degree.

Loehnen writes in her authors note that she “use[s] the words women, woman and we liberally in the following pages. But it’s important that I state clearly: These words are shortcuts for an idea of what it means to be a woman–an idea that can be reductive and essentialist” (ix). In my opinion, this two line statement does nothing to offset the several hundred pages of reductive and essentialist analysis. Loehnen barely talks about Black womanhood until over 100 pages in (notably most explicitly in the “Lust” chapter), and refrains from any true analysis of queer womanhood. This doesn’t even begin to reference the gross acceptance of the gender binary as a whole. All of Loehnen’s efforts to briefly reference some sort of intersectionality, in my opinion, fell flat. Loehnen’s commitment to a non-reductive and non-essentialist arguments was a paradox. Loehnen claims to avoid these problems, but fails to acknowledge intersectionality at all.

It’s my most basic understanding of intersectionality that any effort to discuss one aspect of identity without acknowledging the intersections of multiple marginalizations defeats the purpose of intersectionality at all. Let me give an example. When I call myself an “intersectional feminist,” this is not to say that I am a feminist who acknowledges that people with additional marginalizations are uniquely affected, but rather that there is no universal experience under the patriarchy, and that any effort to generalize completely misses people’s compounding oppression.

What then is the point of On Our Best Behavior? How can any point about the way cultural standards regarding “sloth” be effective if not specifically applied to people’s intersecting identities and compounding oppression? No statement about “sloth” regarding womanhood would feel authentic to a Black woman, a disabled Black woman, a disabled Black woman descended from enslaved people, etc. All of these portions of a human being’s experience are compounding and proliferating, and I found On Our Best Behavior to be unsatisfactory at approaching this topic.

I think I’ve found a bit of trouble with nonfiction social commentary written by journalists and the like. Maybe You Should Talk to Someone, Ghosts of the Orphanage, and We Were Once a Family are all nonfiction books that I’ve read in recent years that I think all struggle with this same issue. Journalism has different standards for sourcing and reporting; I have yet to read a long-form piece (longer than an essay) written by a journalist that I think would stand up to academic scrutiny. An argument can be made that not all “nonfiction” books should be held up to “academic” scrutiny, but I think that if a 23 y/o with a bachelors degree can question the sourcing of a text, its legitimacy, and whether or not it should pose any sort of expert authority, a books “nonfiction” status can deservedly be questioned.

This is not to say that I think that Loehnen made anything up in her book–and there have been scholars who have fabricated evidence. I rather mean that the way in which Loehnen presented information within her book had a particular slant. Media literacy is a key skill, and I’ve reached the point in this review that I’ve realized I’m rambling more about that than about the specific nature of this text. Let me circle back and end here: because On Our Best Behavior was written from a journalistic rather than an academic lens, Loehnen never attempts to discuss or refute an opposing opinion. I would argue that such academic efforts–that would have allowed me to take the book more seriously–were shirked in favor of this book’s commercial appeal.

Overall, worth reading and worthy of discussion!